|

| Patient entering MRI machine |

|

| Orlan undergoing surgery |

This idea of utilizing medicine as not just a mode, but a tool, of art is taken to a new level by the artist Orlan. While I was not surprised by the idea of cosmetic surgery as an artistic method to reshape and sculpt the human form, I was taken aback by the ways in which Orlan stretches the limits of this concept. She utilizes her own body as her medium, to the extent of making unalterable physical modifications to her form in order to express the artistic messages of such forms. Orlan’s tactics reminded me of Casini’s observation that MRI scans help us reconsider the question of “what defines us as humans?” (Casini 75). Manipulating the way we appear and view ourselves gives us new insights into our conception of what comprises not only the human form, but also human identity.

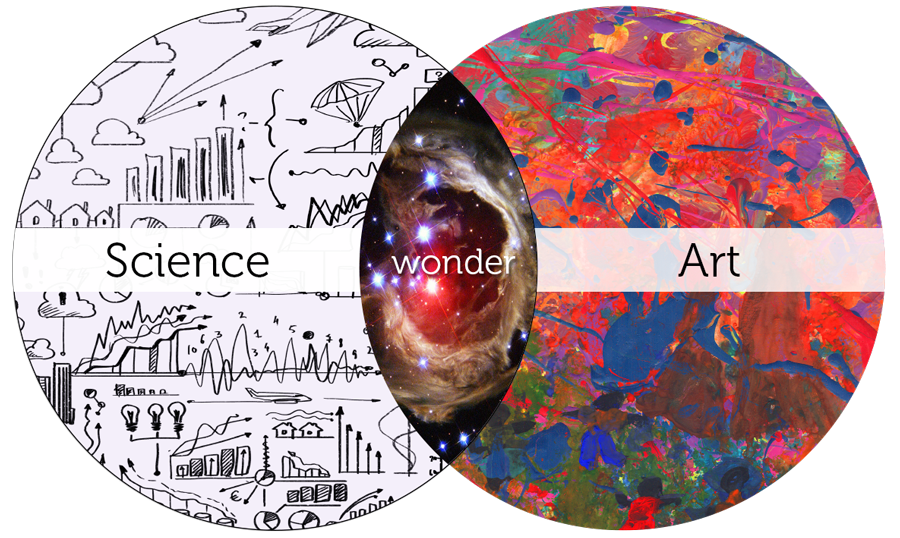

In this way, medicine does not only complement art; it is also an art itself. Even the Hippocratic Oath that is so highly esteemed in the medical field recognizes this relationship, declaring “there is art to medicine as well as science” (Tyson). Indeed, although life, at both the molecular and systemic level, follows a distinct set of rules, these rules are not dissimilar to patterns found in art forms such as architecture (Ingber). When you truly think about the medical practice, it is not a set of scientific protocols; rather, taking on such a role at the interface of advancing knowledge and caring for human beings requires a degree of artistry.

|

| The Art of Medicine |

References

Casini, Silvia. “Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as Mirror and Portrait: MRI Configurations between Science and the Arts.” Configurations, vol. 19, no. 1, 2011, pp. 73-99.

Cleev. “The Art of Medicine.” Deviantart, https://cleev.deviantart.com/art/The-Art-of-Medicine-574781410. Accessed 29 April, 2018.

Ingber, Donald E. “The Architecture of Life.” Scientific American, vol. 278, no. 1, 1998, pp. 48-57.

“MRI scan.” Netdoctor, http://netdoctor.cdnds.net/15/45/980x490/landscape-1446743973-g-examinations493216409.jpg. Accessed 29 April 2018.

Orlan. Carnal Art. YouTube, uploaded by MutleeIsTheAntiGod, 13 Mar 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=no_66MGu0Oo.

“The Artist Who Surgically Modified Her Body To Condemn Our Beauty Standards.” Cultura Colectiva, https://culturacolectiva.com/art/artist-plastic-surgery-beauty/. Accessed 29 April 2018.

Tyson, Peter. “The Hippocratic Oath Today.” NOVA. PBS, 27 Mar 2001, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/hippocratic-oath-today.html. Accessed 29 April 2018.

Vesna, Victoria. “Human Body & Medical Technologies.” YouTube, uploaded by uconlineprogram, 21 April 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep0M2bOM9Tk.